Land Acknowledgement and Community-Engaged Scholarship

“Saying that the university is on Indian land is not enough,” explained Dr. Theresa Stewart Ambo, an Assistant Professor of Education UCSD and member of the Gabrieleno/Tongva and Luiseńo tribes, “We need to take the time to remember.” A graduate of UCLA, Dr. Ambo spoke of her experience as one of the few Native American students on campus.

Dr. Ambo’s historical unpacking of how UCLA came to sit on the land of the Tovaangar tribe is academic scholarship; it is also resistance, refusal to be erased, and a destabilization of colonial histories of “settling” the land. She agrees with feminist Audre Lorde that, “we cannot dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools,” however, she also believes “we just may be able to crack the foundation.”

Taking time to remember. Activating historical analysis. Institutionalizing Land Acknowledgment. At the UCLA James West Alumni Center, the participants of “Lighting a Path Forward: UC Land Grants, Public Memory, and Tovaangar,” on Tuesday, October 15th 2019, embodied the words on the banner that welcomed conference guests: “Our Existence is our Resistance.” Land Acknowledgment at land-grant Universities is not simply about honoring the people who were here before the university was founded, it is also about acknowledging the ongoing violence of settler colonialism, and the survival of the people who land was stolen. It is about resisting the erasure of this history, and acknowledging the presence of indigenous people who attend the university, as well as continue to live and practice their culture in the area. Existence is resistance.

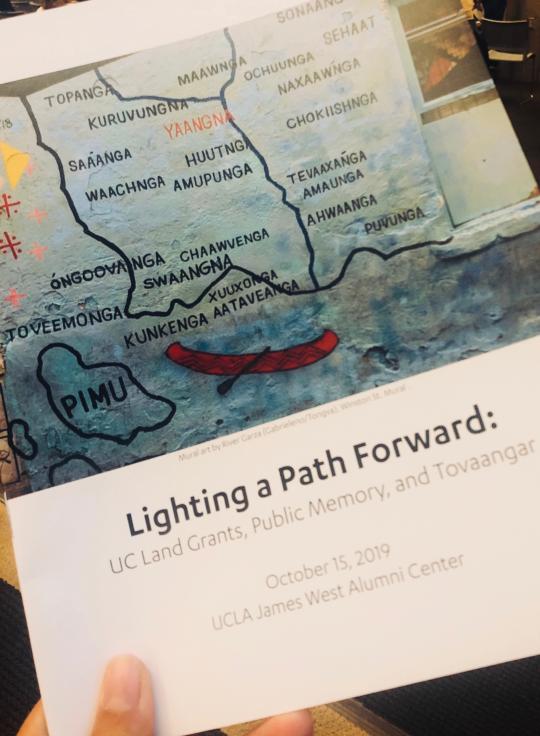

The program cover for

“Lightingthe Path Forward:

UC Land Grants, Public

Memory, and Tovaangar,”

at University

California-Los Angeles.

Native Americans have long been the subjects of research, their stories and cultures appropriated and used by and for the professional and economic advancement of non-Native scholars in academia. At “Lighting the Path Forward” the voices of Native people of California speaking on their experiences and their scholarship were foregrounded in conference presentation and discussion. At Sonoma State, focusing on the recruitment and inclusion of Native scholars, especially people indigenous to the land where Sonoma State now sits, is critical in the development of the department of Native American Studies and local tribe-university relationships. Simultaneously, how can non-Native scholars engage ethically in research in Native American Studies?

At Rutgers University, where I completed my Ph.D. in American Studies two years ago, I was trained in publicly engaged scholarship—I conducted research with police officers and civilians in downtown Newark, New Jersey—and I experienced the value (to the people, and the research) of taking a different approach to research. Publicly engaged scholarship, or community engaged scholarship, is a way for academics to practice anti-colonial methods of research. At “Lighting the Path Forward,” Dr. Robin Maria DeLugan, a sociocultural anthropologist, Associate Professor at UC Merced, and member of the Lenape/Cherokee tribes, promotes community engaged research as a model of scholarship that restructures the traditional researcher-subject hierarchy. She outlined a model for this approach, including taking time to know the community one is interested in learning about and from:

Build trust./Invest time, show up!/Listen to the community’s priorities./Discuss new ways of doing research./Share examples of collaborative research./Recognize that some communities, like some students and researchers, may need training, support and to better collaborate.

This community engaged approach to both education and scholarly production was echoed by multiple presenters, including Dr. Ricardo Torres, Professor Emeritus of CSU Sacramento, and member of the Wintu tribe, who stated, “Relationships are what we are doing.” Following the guidance of these Native scholars and activists, I encourage our faculty and student researchers to consider Dr. Lugan’s questions: “How can we connect our research mission with our region? How can the research benefit the university and the community? How can we make the research applicable, and actionable?” How can de-colonize research methods and scholarly practice?

Theresa Jean Ambo, PhD (Luiseño/Gabrieliño/

Tohono O’odham), Assistant Professor in the

Department of Education Studies at University

of California-San Diego, presents her work on

the history of the land, and the indigenous

people who lived on and tended the land, on

which the University of California-Los Angeles

now sits.

Attending “Lighting the Path Forward” bolstered my inclination to place public scholarship at the center of our growing Native American Studies Department, as the recommendations of Native scholars in the California State University and University of California University systems strongly supported tribe-university academic and social programs and community engaged scholarship. Dr. Cindi Alvitre, Faculty at CSU Long Beach, and member of the Gabrieleno/Tongva tribes and T’iat Society, explained that while indigenous people had once been locked in (to missions and reservation schools), they were now being locked out (of universities). As the Center for Community Engagement (CCE) and the Department of Native American Studies at SSU move forward in collaboration to foster relationships with our local Indigenous nations and communities, we must support Native youth in academic success. This begins long before they step onto campus. Gaining and retaining local Native students at SSU requires social and academic programming that is co-created with tribes, and reaches families and Native youth. To begin to address the violent history of enforced assimilation through schooling, educational institutions in the United States should learn from Native scholars and seek to practice de-colonizing pedagogies and research methodologies.

As the Director of Native American Studies, I am inspired by the alignment of the CCE and Native American Studies Department’s intentions to nurture Sonoma State’s relationships with local tribes. This Spring 2020, we will launch a pilot social and academic support program with the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians. This project invites CCE, NAMS faculty, and Sonoma State students to engage in de-colonizing approaches to education. How can collaborative social and academic programming serve our local Native youth? How might our students at Sonoma State learn through these co-learning experiences? How can our research produce relevant and applicable research that also contributes to the scholarly excellence of Sonoma State University? And we seek to answer these questions, as we engage in the work of relationship building—individually and institutionally—we must remember to listen.

Author: Dr. Erica Tom